Dispersed camping: Your (FREE) ticket to Instagram-worthy campsites without the crowds. But first, we’ll answer common questions. . . like where to poop.

What is Dispersed Camping?

The phrase “What is dispersed camping” is averaging 2,400 hits per month on Google from US searchers alone. Clearly, this is a hot topic. And, when national parks and high competition camping permit statistics look like this:

Arches only has 52 developed campsites and is almost unfailingly booked out every night of the high season (March-Oct.)

Campers generally have to book at least 6 months in advance to get lucky enough to snag a campsite

It makes sense that dispersed camping is having its moment in the limelight.

For those of you who found this article by typing, “What is dispersed camping?” into your search bar, here’s what you’ve been waiting for.

Dispersed camping is free, primitive camping on federally owned land in the US. Dispersed campsites are undeveloped and do not offer any amenities—except the unspoiled beauty of nature. Dispersed camping is typically available anywhere you can find a Bureau of Land Management District, National Forest, or Wildlife Management Areas.

It’s kind of like a wild and wonderful free for all where you can spend the night, or a week, in some of the world’s most picturesque locations, rent-free, and untouched by the plugged-in world around you.

While the possibilities are vast and exciting, there are some rules to dispersed camping that vary depending on the area you’re camping in—check local regulations online when planning your trip or visit a ranger station before heading into the backcountry. There’s also etiquette and leave no trace principles you should know before you go.

Read on for the answers to all your burning dispersed camping questions, including the ones that are too awkward to ask anyone except Google.

When Nature Calls: Tips for dispersed camping

Are the mountains calling and you feel like you just must go? That’s great! It’s time to escape the overcrowded designated campsites and really get out there.

A lot of folks get scared away from primitive camping by some common concerns that I call the Three P’s of primitive.

Pitching Camp. Predators. Pooping.

These look something like,

“Where do I park my car? Do I have to park, hike to my campsite, and pitch a tent? Can I car camp? How do I know I’m in the right place?”

“How do I not get eaten by a bear or mountain lion or [insert predator]?”

“You expect me to poop in a hole!? What are these confusing rules about BYOT (that’s bring your own toilet)? That’s all too much work. I’ll take the campsite with a vault toilet please.”

Pitching Camp, Predators, and Pooping are not as confusing, concerning, and stress-inducing as they may seem. It just takes a few tips, tricks, and a little nature-savvy know-how that we’ll provide for you here, all in one convenient place.

How to find dispersed camping:

Step one: Plan ahead. Know where you’re going before you head out. When you’re dispersed camping you often will find that you’re at least 30 minutes or more from any town, gas stations, cell service, etc. This means Google Maps won’t be able to help you out if you’ve already gotten outside of service range.

Look online and find federal land that you want to camp on ahead of time.

Pro tip: Layer and cross-reference maps. What looks like a great spot to camp on a satellite map may actually be a 40-degree incline on the side of a mountain once viewed on a topographic map. I like to scope out potential campsites on Google Maps ahead of time. Layering maps helps ensure the spot you’ve set your sites on is flat, accessible, and not on private land.

To find federal land online and plan your route ahead of time, use these resources:

The US Forest Service’s interactive map of National Parks and Forests (National Forests are the ones you’re looking for in this case).

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) also offers a map that denotes BLM land designated for specific uses including camping and recreation.

Campendium, Free Campsites, and The Dyrt Pro are all great resources. The Dyrt Pro requires a paid subscription but allows you to download maps for use outside cell service.

Many primitive campsites are accessible by car. Again, do your research ahead of time and cross-reference maps to ensure the area you’ve chosen is clear of trees and undergrowth that might block access by motor vehicle and isn’t on a steep hill or too steep to access in the car you drive.

The great thing about camping on public land is that you can have it your way. Car camp, pitch a tent, toss a sleeping bag in the dirt, it’s up to you.

Just keep in mind to respect the land around you—don’t trample down growth to gain access to the spot you want to pitch camp. Be polite and conscientious of the land, like you would when visiting a friend’s house.

How to not get killed by an animal while camping:

To be honest, there’s only so much you can do. Wildlife is unpredictable and it’s a risk assessment you make before camping in the backcountry.

With that disclaimer out of the way, I’ll mention that mountain lions, wolves, and bears (oh my!) are a much less common sight than you might imagine. If you’ve run into one while camping or hiking on public land, it’s probably as surprised (and scared) to see you as you are to see it, so keep calm and carry on with these things in mind:

If a predator is approaching you, appear as large and threatening as possible. If you have a jacket, hold it open and spread your arms wide, wave your arms above your head, clap, speak loudly and slowly at the animal. It will most likely leave once it realizes you’re not in its diet.

If you have kids or a dog and encounter a predator, pick them up off the ground, if possible, without bending over or turning your back to the wild animal. You don’t want to resemble the four-legged prey that predators hunt.

Never turn your back to a predator. Maintain eye contact and walk backward slowly until it goes away. Never run from them as it will trigger their instinct to chase. . . Be it a wolf, mountain lion, or bear, you won’t beat them in a race.

Keep bear spray on hand. Know how to use it in the unlikely event that you’re charged by a bear.

Always do your best to make your presence known. You never want to startle a dangerous animal.

Keeping food and trash properly secured is the best way to ensure that you don’t face an unexpected run-in with a bear or another predator (or a crafty raccoon) at your dispersed campsite.

Bear canisters are one of the best—and in certain backcountry areas, required—methods of keeping bears from getting into your food and lingering around your campsite. Store food in one bear canister and, if it doesn’t add too much to your load, keep a separate canister to store your trash.

My personal go-to for food and trash storage are bear bags. Secure all food or garbage in odor-proof ziplock bags, close it all up in a bear bag, and use a rope to sling it over a sturdy tree branch, tying the other end of the rope off to the trunk. Make sure it’s high enough that a bear can’t reach the bag from the ground and hangs at least 4-5 feet away from the tree trunk. Note! There is a on-going HOT debate on the effectiveness of bear bags.

Do not ever store food in your tent or your car if you’re sleeping in it. Bears have been known to break into cars to get to food left inside.

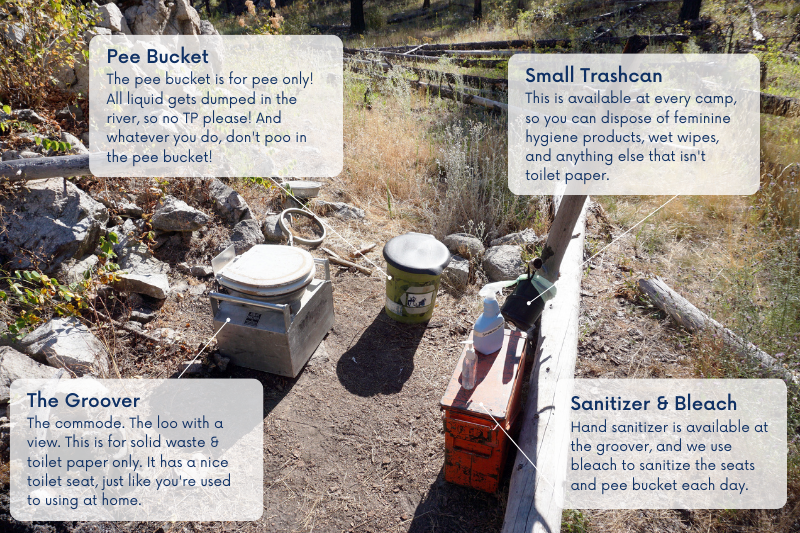

How to do your business in the backcountry

No, this isn’t about how to work remotely from your primitive campsite. This is about pooping in the outdoors. Responsibly. The nagging question I know you’ve been impatiently waiting to put to rest.

You have two options that adhere to Leave No Trace ethics. You can do your business in a hole or a bag. Dealers choice. Kinda. Again, this comes down to semantics and rules that vary from location to location. If you’re in a fragile ecosystem or an area that may face flooding, like a desert canyon or an alpine environment, you will often be required to do your business in a WAG bag.

How to poop in the outdoors:

WAG stands for Waste Alleviation and Gelling. Your WAG bag likely includes toilet paper, sanitizing wipes, and mystery power. The mystery powder is for solidifying and neutralizing the smell of your poop—leave it in there—remove everything else. After removing your clean-up kit, roll out the inner bag liner and make sure it’s wide open (it should look like a poop-tube). Set it on flat ground, squat over the opening of the poop-tube, and do your business. Toilet paper and sanitizing wipes go in the bag with the poop. Seal the inner bag (poop-tube) before rolling and diligently sealing shut the outer bag.

Always pack out used WAG bags in the bottom of your pack or in your trash bag. Once back in civilization you can toss them in the garbage.

Using a Cathole:

This method is relatively straightforward. Bring a lightweight trowel on your dispersed camping trip. When nature calls, find a comfortable spot at least 100 feet (that’s about 70-80 steps) from any water source. Use the trowel to dig a hole at least 4in. wide and 6-8in. deep—pooping in a sunny area will help speed up decomposition. Squat. Empty the tank. Pack out all toilet paper and sanitary wipes in a sealed odor-proof ziplock bag. Once finished, use the loose soil to cover your cathole. Tamp down the top to keep critters out and, if you want to be considerate of other wild-poopers, mark your poo-grave with a stick so nobody else digs there.

Bonus: Peeing outside tips for the ladies.

Squat and pee with your back facing downhill so that the stream runs away from you.

Strategically choose soft earth, like pine needles or loose soil, to pee in so that you don’t get hit by splashback.

A pee funnel like a Sheewee can be used to help you pee in a bottle when it’s late at night or too cold to get out of the tent and drop your drawers.

Introducing my new personal favorite piece of camping gear. Keep a Kula Cloth hooked on the outside of your pack. These antimicrobial pee clothes help cut down on the TP you have to pack out and are much more sanitary than drying off on a bandana.

Keep the Wilderness Wild: The first rule of dispersed camping is to Leave No Trace

Whether you’re hiding your poo or refraining from feeding the wildlife. The ultimate goal when entering the backcountry is to ensure that, upon leaving, no one will ever know you were there.

You might have gotten used to park rangers and campsite managers cleaning up after visitors and emptying vault toilets. When dispersed camping, you’re the only one there to clean up after yourself.

This extends to having campfires as well. You often won’t find permanent fire rings or fire grates when you’re camping primitively on public land. This means that establishing a safe, responsible, and Leave No Trace compliant fire pit is your responsibility. In the case of certain fire restrictions, you cannot have a campfire unless it’s built in a permanent fire pit.

LavaBoxes pass most Stage One and Stage Two fire restrictions and are one of the safest options for enjoying a campfire while camping in dispersed campsites without permanent fire rings. They’re also as easy to pack out as they are to pack in because there’s no ash or burnt ground left behind.

Camping primitively on public lands opens up a whole new world of opportunity. You’ll experience sites and IG-worthy locations that no overcrowded, high-competition permit or reservation-based site compares to. You can get those bucket list pics without having to Photoshop out the other 200 people. All it takes is learning a little, preparing ahead, and possibly stepping outside your comfort zone.

Please remember to practice Leave No Trace and low impact principles at all times. To learn more about these you can visit lnt.org.